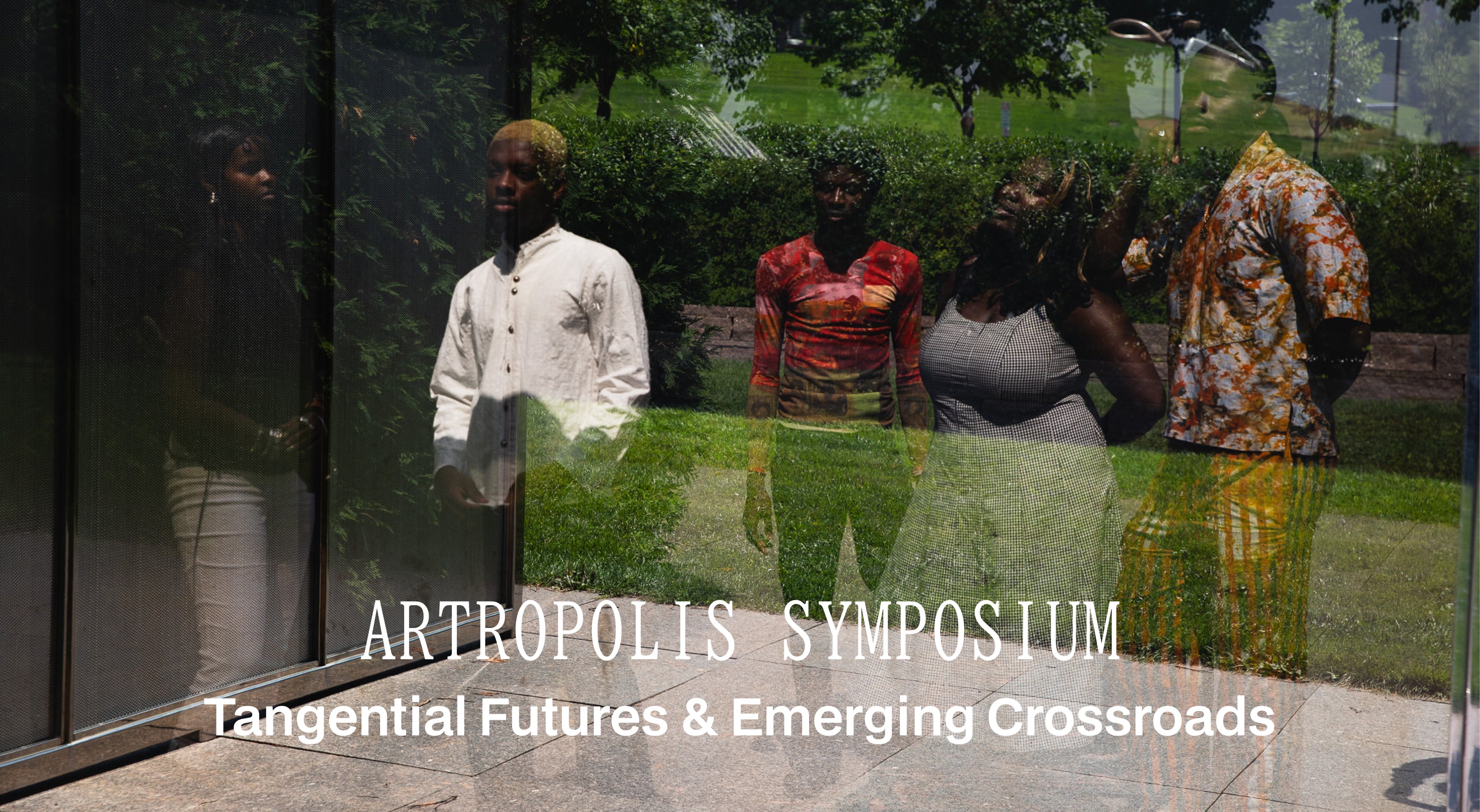

TAOHEED AND RIIYO OF ARTROPOLIS SIT DOWN WITH NICOLE CROWDER TO CONVERSE ON THE CONVERGENCE OF ARTISTIC MINDS WHO DARE TO REIMAGINE THE URBAN LANDSCAPE AS A LIVING BREATHING CANVAS

Nicole Crowder (T): If both of you could share your names, your ages, and where you live in the Twin Cities?

Riiyo (A): My name is Riiyo—well, that’s what I go by colloquially. My government name is Abdullahi. I’m 25, a Minneapolis native, born and raised—everything 612.

Taoheed (A): My name is Taoheed Bayo. Some people call me Tbuzz, but I’m more aligned with Taoheed Bayo these days—it feels professional and staunch. I was born and raised in Lagos, Nigeria, and I moved to Minnesota about 10 years ago. Since then, I’ve explored different art forms—visual art, dance, performance art, bookmaking—and now I’m more focused on community building.

Nicole (T): Wow. Both of you, just from the little research I’ve done, have such varied disciplines. Your mediums are so different, but brilliant. I’m curious: where did your paths intersect? How did you meet, and what connected you?

Riiyo (A): We actually met in what I’d call a “third space,” which is something we’re very interested in fostering. We met at a party called Samambo, led by Kwey (Brandon Mensah), who’s also part of Artropolis. The second time we met was at ItsFest, led by Philli, another member of our Guild. So we met in spaces where convergence was natural. That was about two years ago, September 2023. From there, friendship and deeper conversations grew.

Nicole (T): I love that. So when you first connected, was there an immediate sense of wanting to build something together? Or did it start with your own separate work and then overlap?

Riiyo (A): I think both. We share parallel ways of seeing the world. We both care deeply about what it means to be diasporic kids in America, specifically in Minneapolis. There’s a unique intersection there, and we naturally found resonance with each other.

Artistically, I’ve always been drawn to storytelling—I come from an oral tradition. I’ve been immersed in communal spaces and curating experiences where people can arrive as they are. When we first talked about Artropolis, Taoheed had already been ruminating on the idea from his experiences in global, transnational spaces. We had these long conversations—often by the river—about what the ethos of Artropolis should be: who we’re building for, what it should look like, and how to make it participatory from the start.

We see Artropolis as “city-making.” It’s about transforming and imagining urban landscapes through art, and ensuring the community is woven into that process.

Nicole (T): And who are the people you imagine bringing into this city you’re building?

Taoheed (A): From the beginning, we center Black people and people of color. Representation matters—if you don’t see someone who looks like you doing something, it can feel impossible. For me, accessibility is also key. When we’re at places like the Walker, it’s not just about me—it’s about showing others that these spaces are for them too.

Riiyo (A): And beyond race, it’s about mindset—people who are curious, open, experimental, playful. People who want to build authentic futures. When I think about Artropolis, I see it as a bus: not with one conductor, but many. It’s horizontal, collaborative, open. Everyone’s input helps drive where we go.

“Minneapolis has always been the backdrop. A friend once described it as an umbilical cord—it ties us to the city and makes us want to give back because it has given us so much. What I love about Minneapolis is that it lets your art breathe. Unlike other cities, there’s room here to try, to fail, to experiment. And I think the fear of failure is what kills creativity. Here, I can fail forward.” - Taoheed

The Guild: Taoheed Bayo, Ubah “Riiyo” Abdullahi , Brandon “Kwey” Mensah, Phili Irvin, Awa Mally

Nicole (T): You mentioned meeting by the river and reflecting on the ethos of Artropolis. I also read that water itself has been a muse in your work. Is water an intentional element you’re weaving into the project?

Taoheed (A): Yes. For this activation at the Walker, water was a central influence. We’ve always spoken about water as a witness, a living archive, something that holds persistence and memory. It felt important to showcase that expansiveness—how water connects us as human beings and artists.

Riiyo (R): For me, water also ties into ancestry and spirituality. Philli and I were having conversations about archives—what it means to bring in history, where the “old heads” are, and how those voices shape the present. At the same time, I was thinking about water as a multidimensional being, something sacred to the Dakota, Anishinaabe, and Ojibwe peoples of this land.

Water became the through line—it carries our dreams, our practices, our intentions. I love a Toni Morrison line about the floods in New Orleans—she said water “remembers,” it always finds its way home. That resonated deeply with me. So yes, water is both literal and spiritual grounding for this work.

Nicole (T): I love that framing. And I noticed you’ve incorporated dinners into Artropolis. Was that always part of the concept?

Taoheed (A): I often describe Artropolis as a house with many rooms. At the Walker, we’ve had the chance to open multiple rooms at once.

Earlier this year we did different activations: a sonic experience (Vinyl Night) at Resource Minneapolis, in January, a listening party in February, and an iftar gathering in March that welcomed Muslims and non-Muslims together. For the Walker partnership, we wanted to host a dinner specifically between Black and Native communities—so we could break bread intentionally, share ideas, and imagine how our futures intersect.

Riiyo (R): That dinner was powerful. It wasn’t just about food—it was about creating synergy. People still ask why they weren’t invited because it looked so meaningful. For us, it proved the need for these kinds of spaces. And many of the people at that dinner—like Changó, Baki, Philli, and Kwey—became core collaborators in later workshops and activations. It all grows organically.

Nicole (T): Is there a formal process for people to collaborate with Artropolis, or is it more about natural connection?

Taoheed (A): Definitely the latter. It’s about synergy. For example, Baki’s energy at that dinner stayed with us, so when it came time to invite collaborators, they were one of the first people we reached out to. The body remembers that energy.

So it’s not an application process—it’s about resonance. If someone reaches out with an idea that clicks, we might build an event around it almost immediately. Artropolis has many rooms, so there’s room for everyone in some way.

“It feels like caring for a congregation. To gather people is to become a caretaker. We’re responsible not only for ourselves but for everyone we invite into the space. And it is sacred—to have people of different races, religions, and gender identities come together. We’re learning as we build, but we know it’s holy work.” - Taoheed

Nicole (T): What would you each say are your primary mediums or specialties? And how do those overlap in Artropolis?

Riiyo (R): I think my biggest contribution is framing—holding our work in a container through words and ethos. Much of our content has been processed through me. I also focus on relationships—connecting with people I’ve collaborated with and bringing them in as leaders.

What I care about most is curating experiences. I don’t want people to just attend an event and move on. I want them to be immersed—sonically, visually, spatially—so that they feel charged, so conversations ripple out afterward. Ideally, people see themselves reflected in the space, fueling the work and organically generating future collaborations.

Taoheed (A): For me, Minneapolis has always been the backdrop. A friend (Malanda Jean-Claude) once described it as an umbilical cord—it ties us to the city and makes us want to give back because it has given us so much.

What I love about Minneapolis is that it lets your art breathe. Unlike other cities, there’s room here to try, to fail, to experiment. And I think the fear of failure is what kills creativity. Here, I can fail forward.

Riiyo (R): On your question about third spaces—there are plenty of physical spaces in the city. But for us, the third space isn’t a specific location. It’s an experience we activate. It could be inside an institution like the Walker, where we’re invited to create something dynamic and reciprocal.

Taoheed (A): Of course, maybe someday we’ll have a physical space of our own. But what matters now is being able to bend, morph, and transform whatever space we’re in—into something generative, something that allows for exchange, play, and imagining new futures.

Riiyo (R): Exactly. Third spaces for us are like canvases—voids we get to shape. For example, at the Walker we created a third space installation in the Garden Terrace Room. We combined curated music, art installation, and technology in a way that encouraged people to sit with tensions, not just resolutions.

One installation used medical catheters—normally for measuring heartbeats—transformed into looping videos of natural landscapes. For me, that raised questions about technology, consumption, and ethics in art-making. These are not questions we want to neatly answer, but rather tensions we want people to sit with.

Riiyo (R): That’s why we titled our last conversation Meet Us at the Crossroads. Humanity is on one destructive path, but there are alternative, generative paths rooted in nature and relationality. We want to sit in that tension, invite people into it, and imagine together.

“What I care about most is curating experiences. I don’t want people to just attend an event and move on. I want them to be immersed—sonically, visually, spatially—so that they feel charged, so conversations ripple out afterward. Ideally, people see themselves reflected in the space, fueling the work and organically generating future collaborations.” RIO

WALKER ART CENTER

Artropolis Symposium 3: Soundscapes

Closing Night

Thursday, September 11, 2025

5–9 pm

Walker Art Center

More Info

Nicole (T): What has the response been to the symposiums so far?

Taoheed (A): Honestly, we expected the reception to be good because of the energy we were putting in, but it’s been beautiful. It’s the most Black people I’ve ever seen at the Walker—point blank. And beyond that, the spaces we’ve created invite people to come as they are.

At the first symposium, we had five different activations happening simultaneously: films screening in the Mediatheque, workshops, a simulated third space upstairs with DJs, and even a chess lounge. We wanted art and play to co-exist.

The next ones will continue in that spirit—multiple activations at once. For example, the panel discussion on July 31st was held on the rooftop terrace instead of inside, as a way to radicalize space and challenge norms. There’ll be film, music, dance—because life in community is a social dance.

Nicole (T): Do you see these symposiums as a one-time thing, or will they continue?

Taoheed (A): They’ll continue. We’re applying for grants that will help sustain the work, and what we’ve done at the Walker now serves as proof of concept.

At the same time, we’re global nomads. I was born in Lagos, lived in Europe, and launched my book across six or seven cities. So it’s natural for me to imagine Artropolis in Paris, Accra, Amsterdam, or New York. It’s not forced—the ideas are inherently global. I wouldn’t be surprised if, in six months, someone reaches out wanting us to activate Artropolis in their museum abroad.

Riiyo (R): And yet, at the heart, this is a passion project. We’re doing it for ourselves, because we need these spaces. When we held an iftar gathering in March, we brought together Muslims, non-Muslims, and queer folks in one room. The conversations and laughter just flowed. That’s what feeds us.

Taoheed (A): It feels like caring for a congregation. To gather people is to become a caretaker. We’re responsible not only for ourselves but for everyone we invite into the space. And it is sacred—to have people of different races, religions, and gender identities come together. We’re learning as we build, but we know it’s holy work.

"And it is sacred—to have people of different races, religions, and gender identities come together. We’re learning as we build, but we know it’s holy work" - Taoheed Bayo

Nicole (T): You’ve both talked about caretaking—of spaces, of people. But how do you each take care of yourselves outside of Artropolis? Where do you go to rest, eat, or play in the city?

Riiyo (R): I’ve got one. This is a testament to how organic everything is for us. There’s this beautiful Filipino spot in Mounds View called Kusina. Total mom-and-pop shop. Best chicken adobo I’ve ever had. The set design makes you feel like you’re in the Philippines. And the ube ice cream—out of this world.

Taoheed (A): We still argue about ube ice cream. He was supposed to take one scoop and ended up with five. [laughs]

Riiyo (R): Facts. [laughs] But honestly, what made it special is that when we were planning our dinner series, we ended up going back to them. They didn’t just cater—they showed up themselves. They brought the plates and pots, talked about their culture and food, and how it connects to community. That’s exactly what food should do: gather people.

Taoheed (A): For me, a lot of caretaking happens through travel. I’m a Sagittarius—once I set my mind on something, it’s like it’s already done. So when I plan to rest, I plan big: a beach in South Africa in December, maybe Tanzania after that. Travel helps me reset.

Riiyo (R): Same. Travel is a cheat code. Being somewhere where you don’t hear English—it rewires your brain. It’s like timeline jumping.

Nicole (T): Timeline jumping—I love that.

Riiyo (R): Exactly. And then you bring it back home, like a chef picking up ingredients around the world and cooking with them. It may not taste the same as Bali, but it feeds people here.

Taoheed (A): Even conversations while traveling become mood boards. You come back with new questions or answers you didn’t know you needed.

Riiyo (R): Yeah, it unlocks doors. That’s caretaking for me too.

“I really believe disconnection is the disaster of our time—the idea that someone else’s problem is far away, that what happens to the water or to a community won’t touch me. The antidote is connection. Relating. Planting seeds that grow into networks. Being curious about the intersections—even if they’re awkward or difficult. That’s what excites me: building authentic connections, rooted in care.” - RIIYO

Nicole (T): What’s the experience you hope people have when they encounter you—or Artropolis?

Taoheed (A): I think a lot about offering. We take so much from this world—resources, time, inspiration. So I ask myself, how can I give back? How can I contribute to the ecosystem, not just consume?

What we’re doing won’t resonate with everyone, and that’s okay. But maybe it sparks something in the person who needed to see it. Maybe it tells a younger artist their ideas are valid, that they belong in institutions like the Walker. My hope is that our work is seen as offerings—imperfect, yes, but generous.

Riiyo (R): For me, it comes back to relationality. I really believe disconnection is the disaster of our time—the idea that someone else’s problem is far away, that what happens to the water or to a community won’t touch me.

The antidote is connection. Relating. Planting seeds that grow into networks. Being curious about the intersections—even if they’re awkward or difficult. That’s what excites me: building authentic connections, rooted in care.

Taoheed (A): And connection requires effort. Relationships, ideas, even cities—they need nurturing. We’re all caretakers. We’re all shepherds. The work is to gather intentionally, nurture what we’ve been given, and stay curious.